What Could Cause a Baby to Die 3rd Trimester

Abstract

About two.half-dozen million third-trimester stillbirths occur annually worldwide, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. All the same, the causes of stillbirths are rarely investigated. We performed a retrospective, infirmary-based study in Zhejiang Province, southern China, of the causes of third-trimester stillbirths. Causes of stillbirths were classified using the Relevant Status at Death classification system. From January 1, 2013, to Dec 31, 2018, we enrolled 341 stillbirths (born to 338 women) from 111,275 perinatal fetuses (born to 107,142 women), too as 293 command cases (built-in to 291 women). The total incidence of 3rd-trimester stillbirths was three.06/1000 (341/111,275). There were higher proportions of women with a high body mass index, twins, pregnancy-induced hypertension, assisted reproduction and other risk factors among the antepartum than the control cases. The antepartum stillbirth fetuses were of lower median birth weight and gestational age and had a smaller portion of translucent amniotic fluid than the control cases. The antepartum stillbirth fetuses had a higher frequency of abnormalities detected prenatally and of fetal growth restriction than the command cases. Of 341 cases (born to 338 mothers), the virtually common causes of stillbirth were fetal atmospheric condition [117 (34.3%) cases], umbilical cord [88 (25.8%)], maternal conditions [34 (10.0%)], placental conditions [31 (nine.i%)], and intrapartum [28 (8.2%)]. Merely eight (2.three%), three (0.9%), and two (0.half-dozen%) stillbirths were attributed to amniotic fluid, trauma, and uterus, respectively. In 30 (viii.eight%) cases, the cause of decease was unclassified. In determination, targeted investigation tin ascertain the causes of nearly cases of third-trimester stillbirths.

Introduction

Stillbirth refers to intrauterine death of the fetus during pregnancy or parturition, who was delivered without whatever vital signs. The rate of stillbirths is an important indicator of the obstetric quality and comprehensive medical strength of a state or region. Although the stillbirth rate decreased from 2000 to 2015, in that location were 4.8 million perinatal deaths worldwide in 2015, of which 2.vi million were tertiary-trimester stillbirths and 98% occurred in depression- and middle-income countries (LMICs). It was reported that 36% of tertiary-trimester stillbirths occurred in south-Asian LMICs, and 41% in African LMICsone,2. More importantly, stillbirths have marked socioeconomic consequences, including impairment of the physical and mental health of the parents and the fiscal toll to family and to the healthcare system3. Therefore, the World Health Associates-endorsed Every Newborn Action Program best-selling the need to reduce the number of stillbirths in LMICs, with a target of reducing the number of stillbirths from eighteen.4 per 1000 births in 2015 to 12 per 1000 births by 20304. As one of the largest LMICs, the total incidence of stillbirths in Mainland china is one–4%, and its number of stillbirths is in the top v worldwide5,6. Therefore, China must improve monitoring and reduce the number of preventable stillbirths.

The near effective means of reducing the incidence of stillbirths is to identify risk factors and provide targeted treatment. Pregnancy complications, such as pre-eclampsia and placental abruption, tin pb to stillbirth, as can maternal infectionvii. However, 25–threescore% of stillbirths are unexplained8, possibly because of inadequate evaluation9. A systematic review of stillbirths from 2009 to 2016 in LMICs and loftier-income countries highlighted the poor quality of the data10, which hampers the development of strategies to reduce the incidence of stillbirths. The use of 34 classification systems for the causes of stillbirth undermines our understanding of stillbirth epidemiology. In addition, placental test was performed, in some cases, in two studies from heart-income countries, but not in 28 studies from low-income countries; that method is useful for identifying chance factors11,12. Few loftier-quality biological investigations of the risk factors for stillbirths in LMICs have been performed.

The aim of this retrospective study was to investigate the incidence of third-trimester stillbirths and the chance factors thereof among women who attended the Women's Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Mainland china, from 2013 to 2018. Nosotros wish to provide reliable data that will enable the incidence of preventable stillbirths to be reduced, specially in LMICs.

Results

Incidence of third-trimester stillbirths

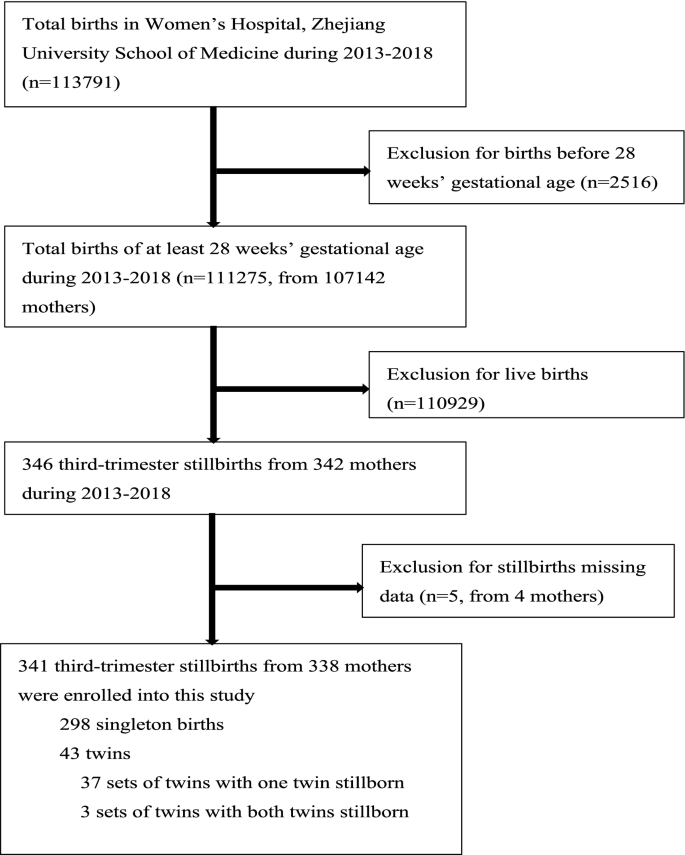

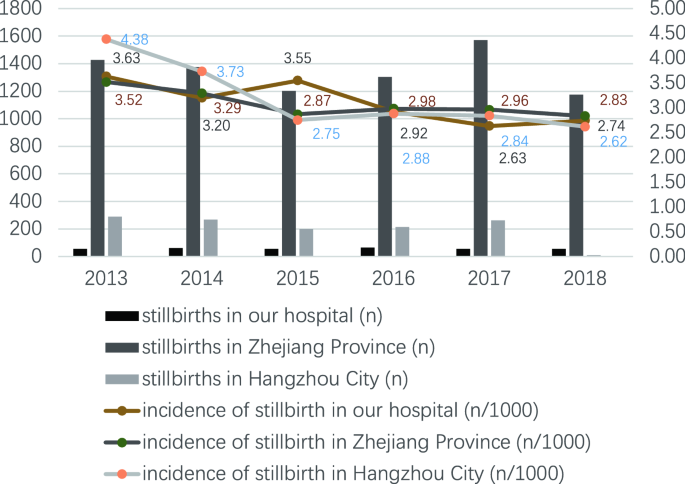

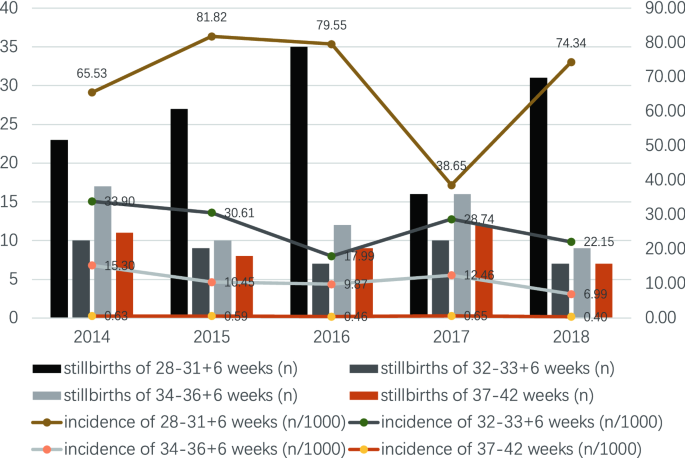

From Jan 1, 2013, to December 31, 2018, the total number of perinatal fetuses delivered in the Women'south Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine was 111,275 (from 107,142 mothers), of which 341 were third-trimester stillbirths from 338 mothers (Fig. 1). The incidence of third-trimester stillbirths was 3.06/yard (341/111,275). The lowest incidence was in 2017 (2.63/thou, 54/xx,533) and the highest was in 2013 (3.63/m, 55/fifteen,134) (Fig. two). The incidence of third-trimester stillbirths was 3.07/1000 in Zhejiang Province and 3.sixteen/1000 in Hangzhou City. Effigy two also presented the specific incidence from 2013 to 2018. The overall incidence of tertiary-trimester stillbirths decreased with increasing gestational historic period in the previous five years: the highest incidence was 81.82/g (27/330) at 28–31 + half dozen weeks of gestational age in 2015, and the lowest was 0.iv/1000 (7/17,675) at 37–42 weeks of gestation in 2018 (Fig. 3). Moreover, the incidence of third-trimester stillbirths varied co-ordinate to demographic features (Supplement: Incidence of tertiary-trimester stillbirths in women and fetuses with different demographic features). These features may exist risk factors for stillbirth (Table S1). Nosotros next analyzed 341 third-trimester stillbirths (338 mothers) and the corresponding controls.

3rd-trimester stillbirths in Women'due south Infirmary, Zhejiang University School of Medicine between Jan 1, 2013 and Dec 31, 2018.

Incidence of 3rd-trimester stillbirths in dissimilar years.

Incidence of 3rd-trimester stillbirths in different years with different gestational historic period.

Baseline demographic and clinical features of women who had stillbirths

Of the 338 women who had third-trimester stillbirths from January one, 2013, to December 31, 2018, 310 were categorized as antepartum cases and the remaining 28 as intrapartum cases; 291 control cases were also analyzed. There were higher proportions of women with a high body mass alphabetize (BMI), minority nationality, primary educational activity level, unemployed occupation, and previous inevitable abortion amidst the antepartum than the control cases. Only three (0.9%) of 338 women had a history of stillbirth (Table 1).

Clinical features during the current pregnancy of women who had stillbirths

At that place were higher proportions of women with twins, no antenatal intendance visit, pregnancy-induced hypertension, assisted reproduction, vaginal delivery, and history of preventing miscarriage amid the antepartum than the control cases. Pregnancy-induced hypertension included hypertension (12, iii.6%), preeclampsia (10, 3.0%), and severe preeclampsia (32, 9.five%). Of the 338 women, 168 had aberrant fetal movement earlier diagnosis of stillbirth (Table 2).

Baseline demographic and clinical features of the stillbirths

Of the 341 third-trimester stillbirths (338 mothers), 313 were antepartum cases and 28 were intrapartum cases; 327 control cases were also analyzed. The antepartum cases were of lower median birth weight and gestational age and had a lower frequency of translucent amniotic fluid than the control cases. The antepartum cases also had a higher frequency of abnormalities detected prenatally and FGR than the control cases. Among the 341 stillbirths, there were 37 deaths of ane twin and half dozen of both twins. Of 298 singleton stillbirths, 97 (32.6%) had FGR (z-score for birthweight for gestational historic period, < − 2). Thirty-six stillbirths were autopsied, of which eight had abnormal findings. Eleven stillbirths underwent array chip testing, of which two had abnormal findings (Tabular array 3).

Macroscopic and histological placental observations in stillbirths

The cord abnormalities comprised cord knots, cord hyper helix, cord torsion, cord entanglement, cord rupture, rupture of cord vessels, and others. Chorioamnionitis was histologically confirmed in 26 (40.6%) of 64 placentas tested. Among 24 of those cases (24/26, 92.three%) four were grade I, eight were grade II, and 12 were grade III co-ordinate to the extent of inflammatory cellular infiltration of the placenta (Table 4).

Risk factors for third-trimester stillbirth

Using the ReCoDe system, in 311 (91.2%) of 341 cases, the third-trimester stillbirth was attributed to a single underlying condition, whereas no crusade was evident in 30 (viii.8%) cases (Tabular array v). Overall, third-trimester stillbirths were most commonly attributed to the fetus [117 (34.3%) cases; 51 (15.0%) with FGR and 42 (12.three%) with lethal congenital bibelot], umbilical cord [88 (25.8%) cases; 58 (17.0%) with other weather condition (eastward.1000., string hyper helix/torsion and short cord)], mother [34 (10.0%) cases; xvi (4.7%) with hypertensive diseases in pregnancy and viii (2.three%) with diabetes], placenta [31 (9.1%) cases; 18 (5.3%) with placental abruption and eight (2.3%) with placental insufficiency], and intrapartum [28 (8.two%) cases; 25 (vii.3%) with asphyxia and three (0.9%) with nascency trauma]. Only eight (2.3%), three (0.9%), and two (0.half dozen%) stillbirths were attributed to amniotic fluid, trauma and uterus, respectively.

The 51 cases of FGR comprised 35 cases of singleton FGR, eight cases of SIUGR (selective intrauterine growth brake), and eight cases of DCDA (dichorionic diamniotic). Among the B-umbilical cord causes, B4 (umbilical cord-other) were most common [58 (17.0%) cases], comprising 50 cases of cord hyper helix/torsion, three of curt umbilical cord, two of single umbilical artery, one of cord entangled past the amniotic band, one of string atresia, and one case of cord cyst. Of the intrapartum causes, 25 stillbirths were attributed to acute asphyxia considering of sudden rupture of cord vessels (four cases), hypertensive diseases in pregnancy (5 cases), lethal built anomaly (four cases), cord prolapse (three cases), FGR (three cases), placental abruption (two cases), placental insufficiency (two cases), hyper helix of the umbilical string (one case), and not-immune hydrops (one instance).

Distribution of stillbirth causes in different gestational weeks

Most of the third-trimester stillbirths caused by fetal conditions occurred at 28–31 + 6 weeks of gestation, accounting for 43.4% (66/152), which was significant (P = 0.002). Virtually third-trimester stillbirths caused by umbilical cord occurred at 37–42 weeks of gestation, accounting for 47.4% (27/57), which was also significant (P = 0.000). The lowest frequency of third-trimester stillbirths caused by maternal conditions was at 37–42 weeks of gestation, accounting for 3.5% (2/57), but this was non significant. Like results were obtained for other factors. The lowest frequency of third-trimester stillbirths caused by placental factors occurred at 32–33 + 6 weeks of gestation, accounting for 3.seven% (two/54), and a tendency toward a higher incidence of third-trimester stillbirths of intrapartum causes at 37–42 weeks of gestational age was observed, accounting for 12.three% (vii/57), merely this was not significant (Table 5).

Discussion

The incidence of stillbirth in the Women'due south Hospital, Zhejiang University Schoolhouse of Medicine from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2018, was 3.06/1000 (2.63–3.63/1000), lower than the national rate in previous reportsv,6. Stillbirth was considered in relation to maternal age, education level, social status, and antenatal care of pregnant women13,14. Nosotros institute that 78.eight% of mothers were of an appropriate age (20–34 years) and 58.half dozen% had a college or postgraduate degree. Furthermore, 13.0% of the significant women did non have regular antenatal care, and 4.one% of the mothers with stillbirth were engaged in physical labor. The mature obstetric techniques and extensive experience of prenatal care in our hospital may explicate the depression rate of stillbirths.

Collecting high-quality data and applying a reliable classification organization institute the starting time step in understanding the causes of stillbirth. Our understanding of stillbirth causes in LMICs is based on analysis of registration data, not investigation of the placenta or dissection of the fetus. A systematic review of stillbirths from 2009 to 2016 highlighted the poor-quality data to determine the cause of stillbirths10. Although placental test is highly informative, it was not performed in studies from low-income settings, and in simply two small-calibration studies in middle-income settings. An investigation of 2847 stillbirths in 7 low-income countries using a computer-based hierarchal algorithm based on medical records15 and did non include a biological investigation of the placenta or autopsy of the fetus. Notably, the underlying causes of stillbirths were not fully characterized because biological investigations were not conducted. In this retrospective study, we reviewed bachelor maternal and fetal medical records during pregnancy and commitment, and undertook macroscopic and histological examination of the placenta, and autopsy and array flake testing of the fetus. Unfortunately, only 64 of 341 stillbirths were subjected to placental examination. The recommended fetal autopsy charge per unit is > 75%. However, the reported dissection charge per unit is 5.8–58% for various reasons, including religion, cognition of stillbirths, and the educational level of pregnant women16. In this study, but 36 autopsy cases (10.6%) were reported. In add-on, ii abnormal results were found amid eleven stillbirths subjected to array chip testing, but the abnormality was non directly related to the clinical phenotype. The cause of stillbirth once was classified as B2 (constricting loop of umbilical cord), and the other as I1 (no relevant condition identified).

The aforementioned systematic review of stillbirths published in 2018 also highlighted the inconsistent apply of nomenclature systems for causes of stillbirths. A variety of classification systems are bachelor17,18. The pass up in the stillbirth rate in high-income countries has slowed or stopped during the terminal few decades afterwards decreasing past 2-thirds from 1950 to 197519. Standardization of classification systems is required to meliorate our understanding of stillbirth. In 2011 the authors of the Lancet Stillbirths Series suggested that classification should exist the main focus of epidemiological measurement research20. For each stillbirth, many possible causative weather are present, and integrating the information is challenging. The ReCoDe nomenclature organizes clinical information related to stillbirth rather than the cause of expiry21. The purpose of ReCoDe is to avoid a case-past-instance analysis and information technology enables retrospective classification using databases. Although ReCoDe is less clinically constructive than a case-by-case perinatal review22, it is less time-consuming, tin can exist performed retrospectively, and accounts for inconsistencies among researchers, countries, and periods. Some other advantage of the ReCoDe system is its ICD-code-based structural hierarchy, resulting in 85% of stillbirth cases meeting relevant weather condition. However, it follows a pre-established bureaucracy, irrespective of whether some other condition made a greater contribution. In 2009, amongst the six stillbirth nomenclature systems evaluated by the International Stillbirth Alliance23, RECODE ranked tertiary. The optimum nomenclature system should collect every bit much relevant information equally possible, using a hierarchical method as a guide only still rely on skillful advice24.

We evaluated the RECODE classification in a retrospective analysis of 3rd-trimester stillbirths. The rate of unexplained cases (30/341, 8.8%) was slightly lower than that in a West Midlands cohort of 2625 stillbirths, an Italian sample of 154 stillbirths, a Dutch sample of 485 antepartum singleton stillbirths, and a French sample of 969 stillbirths (sixteen.0, fourteen.3, 14.2, and thirteen.9%, respectively)20,21,25,26. Nosotros reported a 12.3% (42/341) charge per unit of lethal congenital anomalies, similar to the finding of Gardosi, but the rate of stillbirths classified as FGR (A7) was significantly lower (15.0% versus 43.0%). In the three other case series, the rate of FGR was xxx.3%, 16.9%, and 38.ii%xx,25,26. The differences may be a outcome of population enrollment and different definitions of FGR. The rate of FGR stillbirths may have been slightly underestimated in this report.

FGR is a mutual obstetrics complication. It is typically associated with adverse outcomes such equally premature nascency, stillbirth, and neonatal expiry. The incidence in the United States and Europe is v–15%27, while that in China is similar to that of adult countries. Of the above-mentioned half dozen stillbirth nomenclature systems, but the ReCoDe system classifies FGR separately23. Of the 341 cases of third-trimester stillbirths, there were 97 cases of FGR in single fetuses [32.vi% (97/298)], and 27 cases of FGR in twin fetuses [62.3% (27/43)]. Among them, 73 stillbirths had other conditions that were greater contributors than FGR, such equally maternal status (including F4-astringent pre-eclampsia, F1-gestational diabetes with poor glycemic control), fetal condition (including A1-fetal built anomaly, A3-fetal non-immune hydrops), placental status (including C4-severe placental insufficiency, C1-placental abruption), umbilical factors (including B1-umbilical cord prolapse, B4-umbilical vascular rupture) and intrapartum (G), while the remaining 51 cases were classified as fetal growth restriction (A7). Termination of pregnancy according to the fetal condition is the mainstay of treatment for FGR. FGR pregnant women with abnormal doppler measurement of blood catamenia in the ductus venosus (DV) accept a significantly increased incidence of stillbirth. The combination of fetal move and ultrasound monitoring of blood flow parameters tin can reduce the incidence of FGR28.

A meta-analysis concluded that stillbirths in depression-income countries were attributable to infection (fifteen.8%), hypoxic peripartum expiry (11.vi%), antepartum hemorrhage (ix.five%), and other unspecified conditions (13.8%); 41–44% were unexplained10. In a written report in seven low-income countries15, the main causes of stillbirth were asphyxia (46.vi%), infection (20.8%), built anomalies (8.four%), prematurity (6.6%), and unidentified (xi.eight%). Infection was the leading cause of stillbirth in all of the in a higher place studies. In this piece of work, the rate of chorioamnionitis (D1) was two.1% (7/341), significantly lower than reported by others. The differences could be caused by inconsistent apply of classification systems. In item, the overall incidence of stillbirths in Cathay has reached the level of high-income countries, and so the nomenclature of causes of stillbirths has become similar to that in high-income countries. Amidst the seven cases of chorioamnionitis, two were clinically diagnosed, and the other v had pathological findings upon placental examination. In this study, among 64 cases in which placental pathology was evaluated, 26 cases of chorioamnionitis were histologically confirmed. Excluding the five cases mentioned above (D1), those 21 cases were classified as follows: 10 cases as umbilical cord-other (B4), two equally constricting loop of umbilical cord (B2), two as lethal congenital anomaly (A1), two every bit hypertensive diseases in pregnancy (F4), two as diabetes (F1), one as placental insufficiency (C4), i as infection of fetus (A2) and one as intrapartum asphyxia (G1).

Although this study was conducted in an HBV-endemic area, no stillbirth was attributed to HBV. The incidence of third-trimester stillbirths was similar in HBV-negative (0.317%, 317/99,879) and HBV-positive (0.289%, 21/7263) pregnant women. Furthermore, five women were seropositive for syphilis, and four stillbirths were attributed to syphilis (A2-infection of fetus); the other was attributed to other conditions (A7-fetal growth restriction). The iv syphilis-seropositive women classified as A2 (infection of fetus) did not attend routine antenatal intendance in our hospital. Three of them had stillbirths at the time of diagnosis of syphilis, and ane had been treated with benzylpenicillin for 4 weeks in another hospital only had a titer of 1:sixteen. The syphilis-seropositive woman classified as A7 (fetal growth restriction) was treated with ii courses of benzylpenicillin in a foreign hospital for v weeks, and had a titer of 1:1. Otherwise, the incidence of third-trimester stillbirth in syphilis-seropositive meaning women (2.793%, 5/179) was significantly college than that in syphilis-seronegative pregnant women (0.311%, 333/106,963). This emphasizes the importance of syphilis screening and treatment.

The above-mentioned studies reported a 46.half dozen% rate of asphyxia and 11.six% of hypoxic peripartum death10,xv, an important cause of stillbirth. Abnormal conditions of the mother, placenta, and umbilical cord (e.g., preeclampsia, placental abruption, and umbilical cord prolapse) may cause fetal hypoxia, asphyxia, and death. In this study, the charge per unit of asphyxia (G1) was 7.three% (25/341), significantly lower than reported previously. In the ReCoDe nomenclature organisation, asphyxia is in the G1 subcategory of the M category (intrapartum). Among the 28 (viii.2%) cases of Thou category (intrapartum), 25 stillbirths were attributed to acute asphyxia (G1) and the other three to nascence trauma (G2), all of which were breech deliveries prior to 34 weeks. In fact, other conditions made greater contributions to stillbirths in these three cases of nativity trauma just were classified as G2 because the directly crusade was breech delivery. The same is true of 25 cases of acute asphyxia (G1), which were classified as sudden rupture of cord vessels (four cases), hypertensive diseases in pregnancy (five cases), lethal congenital bibelot (four cases), string prolapse (3 cases), FGR (three cases), placenta abruption (two cases), placenta insufficiency (2 cases), hyper helix of umbilical string (i case), and non-allowed hydrops (one example). Early detection and treatment of complications during pregnancy (e.1000., preeclampsia, FGR), enhanced fetal monitoring during birth (fetal eye charge per unit monitoring, ultrasound monitoring), and rational employ of midwifery applied science (cesarean section, forceps, head-up attraction, perineal side cut), can reduce the incidence of intrapartum stillbirths by 45%29.

Placental investigation showed that nine.1% (31/341) of stillbirths were attributed to placenta (C), and 2.three% (8/341) to placental insufficiency (C4). The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network written reporteleven showed that placental exam tin diagnose 64.six% of stillbirths. A prospective, observational study in S Africa30 involved macroscopic and histological examination of the placenta and culture of fetal blood. These examinations should exist considered for time to come studies in LMIC settings. Our findings highlight the need for systematic investigation of stillbirth, including investigation of the placenta and medical records.

This study had several limitations. Commencement, we did not utilize methods of determining the causes of stillbirth, such as antiphospholipid antibody testing (useful in 1.1% of cases), fetal-maternal hemorrhage testing (6.4%), and testing for bacteria (such every bit group B Streptococcus)31. We tested a small number of women for viruses (such as parvovirus B), which have been implicated equally causes of stillbirths32. In addition, a complete autopsy (36/341) and karyotyping (xi/341) were performed in a few cases, although those enabled identification of the crusade of stillbirth in 42.3% and 11.9% of cases. The limited placental investigation may attribute to limited placental cause. Second, we retrospectively abstracted maternal and fetal clinical information from available medical records. Therefore, incomplete medical records may accept contributed to unclassified (I) stillbirths (8.8%). Third, this was a unmarried-center study. Although our research center is the largest in Hangzhou, cooperation with other research centers would brand our findings more generalizable. 4th, a larger control group may have been better.

Targeted investigation tin can ascertain the causes of most tertiary-trimester stillbirths, reducing the incidence of stillbirths globally. We performed this written report to obtain reliable medical bear witness that could be used to reduce the rate of preventable stillbirths. Although our findings provide important insight into the causes of 3rd-trimester stillbirth, the results may non be generalizable to other resource-poor areas. For case, in areas where interventions such as caesarean section are hard to obtain, the charge per unit of intrapartum causes of stillbirth may exist higher. Farther studies in various LMIC settings are needed to improve our understanding of the strategies, interventions, and research priorities necessary for achieving the goals of the 'Every Newborn Action Plan' by 2030.

Methods

Definition of stillbirth

The gestational weeks definition of stillbirth varies among countries and is ≥ 20 gestational weeks in high-income countries because of their advanced neonatal intendanceii. The Globe Health Arrangement (WHO) defines stillbirth as fetal death at ≥ 28 weeks of gestation, 1000 g nativity weight, or 35 cm birth length—the International Classification of Diseases definitions of third-trimester stillbirth33. Several factors affect the incidence of stillbirths, and the risk factors vary according to gestational weeks. In this study, we defined 3rd-trimester stillbirths as fetal decease at ≥ 28 gestational weeks.

Procedures

This retrospective written report was conducted at the Women's Hospital, Zhejiang Academy School of Medicine, where 111,275 perinatal fetuses were delivered from January one, 2013, to December 31, 2018. We recruited only fetuses with a gestational age of at to the lowest degree 28 weeks. Gestational historic period staging was based on the terminal menstrual catamenia date and obstetric ultrasound in the commencement trimester. Excluding those without complete data, a total of 338 women who had third-trimester stillbirths were enrolled, and 291 women with alive births formed the control group, which were randomly selected from within the same period as the stillbirths, matched on date.

The maternal and fetal clinical information of the cases was abstracted from the medical records. The information was collected by a member of the study staff and was reviewed by a physician researcher using a standard information-collection form.

The data collected included: (1) General information: age of delivery, nationality, instruction level, domicile, stable occupation, weight, height, and body mass alphabetize of significant women; (2) antenatal care visit, gestational weeks, parity, style of conception, multiple gestation, chorionic properties of twins, history of adverse contact in early pregnancy, history of preventing miscarriage; (3) history of maternal diseases, history of uterine surgery, complications of previous pregnancy, complications of current pregnancy; (four) previous inevitable abortion, spontaneous abortion, recurrent abortion or stillbirth; (5) genetic or structural aberration of the fetus, fetal growth restriction (FGR); (6) pathological conditions of the umbilical cord; (7) pathological conditions of the placenta; (8) laboratory indicators: TORCH virus, parvovirus, genital tract pathogens, prenatal screening, ABO claret group, Rh claret group, maternal syphilis, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus test, blastoff-fetoprotein, oral glucose tolerance test, glycated hemoglobin, thyroid function, triglyceride, total cholesterol, glycocholic acid, total bile acids, hemoglobin, coagulation role; (nine) clinical manifestations; (ten) timing of stillbirth (antepartum/intrapartum); (xi) commitment conditions: mode of delivery, neonatal weight, neonatal sexual practice, amniotic fluid, neonatal appearance, macroscopic observation of umbilical string and placenta; (12) macroscopic ascertainment of umbilical cord and placenta, assortment test, and autopsy; and (13) maternal adverse outcomes.

The study was approved by the Human Research Ideals Committee of the Women's Infirmary, Zhejiang Academy School of Medicine. The Human being Research Ethics Committee agreed that this report is exempt from informed consent because there volition exist no additional adverse effects on participants, and the investigator will strictly observe the principle of confidentiality, and the relevant written report data will only be accessible to the investigator. The methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Laboratory procedures

The placenta was retrieved and examined macroscopically after delivery. The placenta, membranes, and umbilical string were immersed in ten% buffered formalin and transported to the Pathology Department of the Women'southward Hospital, Zhejiang Academy School of Medicine. Portions of placenta selected by the histopathologist were embedded in paraffin and processed for routine hematoxylin and eosin staining, using the standard protocols for placental and umbilical cord assessment.

After delivery, a strip of muscle tissue (1 cm) was resected from the thigh and placed in a sterile container for testing using the CytoScan Hard disk Array Bit (Affymetrix Company) past the Department of Reproductive Genetics of our infirmary. The CytoScan Hard disk Assortment Chip contains 75,000 unmarried nucleotide polymorphism markers and 19,000 re-create number variation markers. They focus on chromosomal microdeletions, duplications, and abnormalities, as well equally subtendyme deletions, of known clinical significance.

After delivery, the dead fetus was transported to the Pathology Section for autopsy for assessment of full general built defects, morphological deformities, and subtle abnormalities. Autopsy can besides identify infection, anemia, hypoxia, and metabolic abnormalities.

Determination the single cause of stillbirths

Individual cases were reviewed past at least two obstetricians and the causes of third-trimester stillbirths were categorized by the Relevant Condition at Expiry (ReCoDe) classification system. The ReCoDe classification includes nine categories from A (fetal atmospheric condition) to I (unclassified), each of which is divided into several subgroups, for a total of 37 subcategories. Although multiple medical weather may be associated with third-trimester stillbirth, each third-trimester stillbirth was assigned a single crusade.

Each case of tertiary-trimester stillbirths was discussed by the expert group in our hospital based on all available data (including clinical, pathological, genetic, autopsy, etc.), confirmed the single cause and recorded.

Statistical analysis

Chiselled variables are presented as frequencies (%). The demographic and clinical features of mothers and fetuses were compared by χtwo test, equally were adventure factors for stillbirth co-ordinate to number of gestational weeks. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 software. A value of P < 0.05 was regarded as indicative of statistical significance.

Information availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

References

-

Blencowe, H. et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 4, e98–e108 (2016).

-

Lawn, J. Eastward. et al. Stillbirths: rates, hazard factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 387, 587–603 (2016).

-

Heazell, A. E. et al. Stillbirths: economic and psychosocial consequences. Lancet 387, 604–616 (2016).

-

WHO & UNICEF. Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable newborn deaths. June 30, 2014. http://world wide web.everynewborn.org/Documents/Every_Newborn_Action_Plan-ENGLISH_updated_July2014.pdf. Accessed 29 March 2018.

-

Chen, D., Cui, Southward., Liu, C., Qi, H. & Zhong, N. Stillbirth in Communist china. Lancet 387, 1995–1996 (2016).

-

Zhu, J. et al. Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of stillbirths in China: a census of nearly 4 million wellness facility births between 2012 and 2014. Lancet Glob. Healt. iv, e109–e118 (2016).

-

McClure, Eastward. Thou., Nalubamba-Phiri, Chiliad. & Goldenberg, R. L. Stillbirth in developing countries. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 94, 82–xc (2006).

-

Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Grouping. Causes of decease among stillbirths. JAMA. 306, 2459-68 (2011).

-

Man, J. et al. Stillbirth and intrauterine fetal death: factors affecting decision of cause of death at autopsy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 48, 566–573 (2016).

-

Reinebrant, H. E. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth. BJOG 125, 212–224 (2018).

-

Page, J. M. Diagnostic tests for evaluation of stillbirth: results from the Stillbirth Collaborative Enquiry Network. Obstet. Gynecol. 129, 699–706 (2017).

-

Aminu, M. et al. Causes of and factors associated with stillbirth in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. BJOG 121, 141–153 (2014).

-

GBD 2015 Child Bloodshed Collaborators. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and nether 5 mortality, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the global brunt of disease study 2015. Lancet. 388, 1725–1774 (2016).

-

Lawn, J. E. et al. Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make the data count?. Lancet 377, 1448–1463 (2011).

-

McClure, E. M. et al. Global Network for Women's and Children'southward Health Research: probable causes of stillbirth in low- and middle-income countries using a prospectively defined classification organisation. BJOG 125, 131–138 (2018).

-

Auger, N., Tiandrazana, R. C., Healy-Profitós, J. & Costopoulos, A. Inequality in fetal dissection in Canada. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 27, 1384–1396 (2016).

-

Gordijn, Due south. J. et al. A multilayered arroyo for the assay of perinatal bloodshed using different classification systems. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 144, 99–104 (2009).

-

Reddy, U. M. et al. Stillbirth classification—developing an international consensus for research: executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Man Development workshop. Obstet. Gynecol. 114, 901–914 (2009).

-

Flenady, V. et al. Stillbirths: the fashion forwards in high-income countries. Lancet 377, 1703–1717 (2011).

-

Ego, A. et al. Stillbirth nomenclature in population-based data and role of fetal growth restriction: the example of RECODE. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13, 182 (2013).

-

Gardosi, J., Kady, Southward. G., McGeown, P., Francis, A. & Tonks, A. Classification of stillbirth by relevant condition at death (ReCoDe): population based cohort written report. BMJ 331, 1113–1117 (2005).

-

Frøen, J. F. et al. Causes of decease and associated atmospheric condition (Codac): a utilitarian arroyo to the nomenclature of perinatal deaths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth nine, 22 (2009).

-

Flenady, V. et al. An evaluation of nomenclature systems for stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 9, 24 (2009).

-

Dudley, D. J. et al. A new system for determining the causes of stillbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 116, 254–260 (2010).

-

Korteweg, F. J. et al. A placental cause of intra-uterine fetal expiry depends on the perinatal mortality classification system used. Placenta 29, 71–80 (2008).

-

Vergani, P. et al. Identifying the causes of stillbirth: a comparison of iv classification systems. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199, e311-314 (2008).

-

Gaccioli, F. & Lager, S. Placental Nutrient transport and intrauterine growth restriction. Front. Physiol. 7, forty (2016).

-

Malacova, E. et al. Risk of stillbirth, preterm delivery, and fetal growth restriction following exposure in a previous birth: systematic review and meta-assay. BJOG 125, 183–192 (2018).

-

Warland, J., Mitchell, E. A. & O'Brien, L. M. Novel strategies to forestall stillbirth. Semin. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 22, 146–152 (2017).

-

Madhi, Southward. A. et al. Causes of stillbirths amidst women from South Africa: a prospective, observational study. Lancet Glob. Health seven, e503–e512 (2019).

-

Nan, C. et al. Maternal group B streptococcus-related stillbirth: a systematic review. BJOG 122, 1437–1445 (2015).

-

Goldenberg, R. L. & Thompson, C. The infectious origins of stillbirth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 189, 861–873 (2003).

-

World Health Organization (WHO). International Classifications of Diseases (ICD). Available at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. Accessed seven March 2014.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and Z.L. conceived and designed this project; Y.H. and Q.West. did the analysis and wrote the manuscript; D.C., L.Q. and Z.L. supervised this project; J.L. and D.H. helped analyzing the data; Y.Z., J.L. and Y.W. helped to collect data. All authors have contributed to read and agreed the concluding content of manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher's notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as yous requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third political party fabric in this article are included in the article'south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If fabric is not included in the article's Artistic Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, y'all will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Wu, Q., Liu, J. et al. Risk factors and incidence of third trimester stillbirths in China. Sci Rep 11, 12701 (2021). https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41598-021-92106-one

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92106-1

Comments

Past submitting a annotate you lot concur to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you lot find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it equally inappropriate.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-92106-1

0 Response to "What Could Cause a Baby to Die 3rd Trimester"

Post a Comment